by Peter Sigrist

The second post in a series on public parks in Moscow, this is a brief visual exploration of urban development leading up to the October Revolution of 1917.

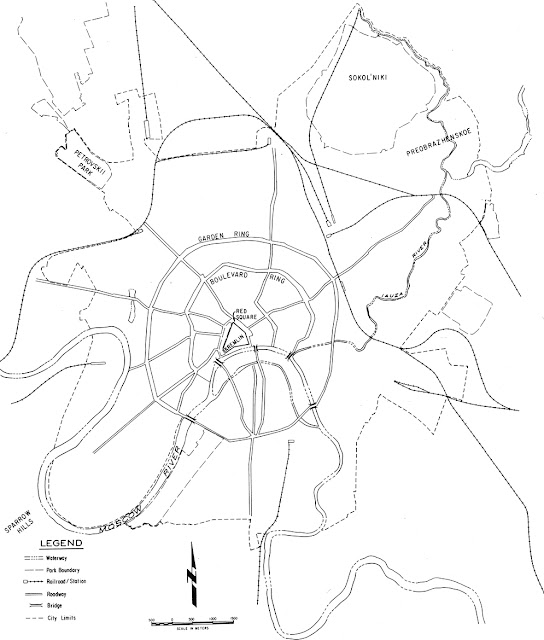

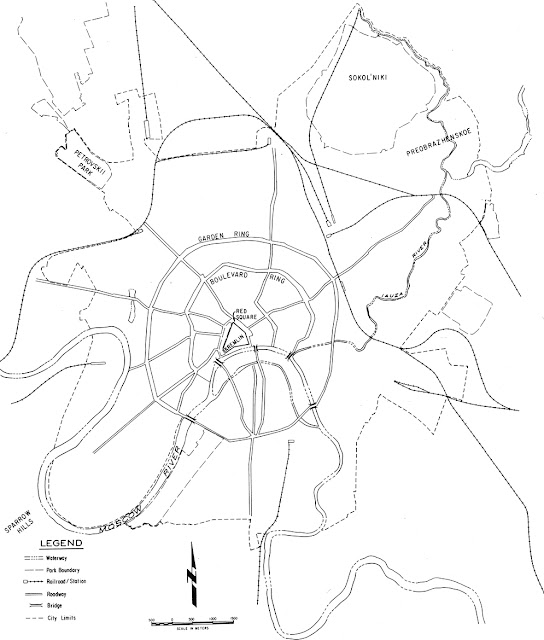

Map of Moscow, 1894.

Map of Moscow, 1894.

Moscow's Kremlin was constructed in 1156 to protect the aristocracy, clergy, traders, and artisans living in its center at the time. The surrounding plains made the city highly vulnerable to attack, so expansion required protective embankments in the form of concentric rings. Moscow grew in stature as the great cities of Kievan Rus declined. Its grand princes (later known as tsars) led the resistance to Mongol rule, and the city was almost completely destroyed numerous times in the process. Russia managed to regain independence by the end of the fifteenth century.

Moscow proved very different from the relatively democratic cities of Kievan Rus. The grand princes ruled autocratically. In order to prevent other nobles from limiting their power, they gave land and laborers to a lower-order gentry in return for allegiance. Thus, serfdom was ingrained in Russia as it was falling out of practice in Western Europe. The landed gentry extracted income from their serfs and provided a military force for the tsars.

Illustration from an edition of Krylov's Fables, by Georgi Narbut.

Under this system, Ivan the Great and Ivan the Terrible strengthened the protective walls surrounding the Kremlin, Kitai Gorod (the market area east of the Kremlin), and Bely Gorod (White City, within the current Boulevard Ring); a new embankment was built around Zemlyanoy Gorod (Earthen City, within the current Garden Ring), and monasteries, estates, and artisan communities were established beyond the rings.

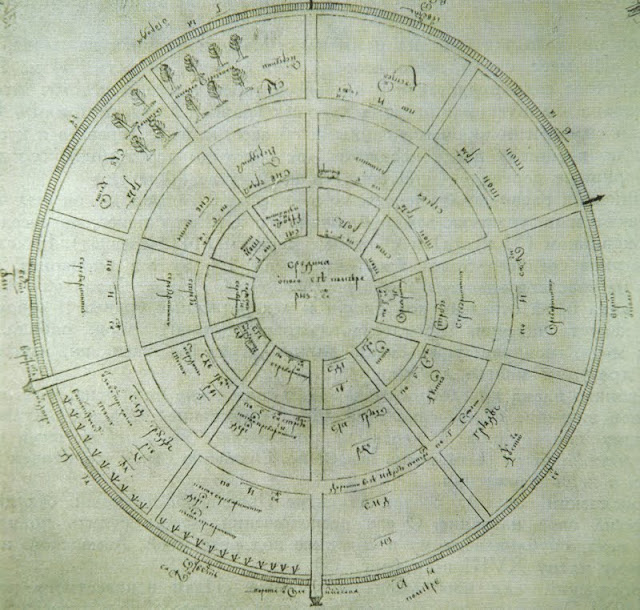

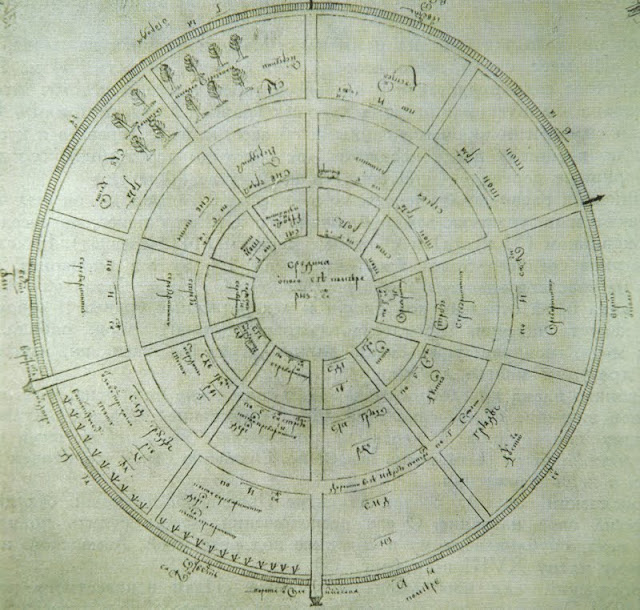

Plan of the seventeenth-century Apothecary's Garden at Izmailovo.

Plan of the seventeenth-century Apothecary's Garden at Izmailovo.

Peter the Great spent much of his childhood at his father's Izmailovo estate on the outskirts of Moscow. He traveled throughout Europe, absorbing modern ideas and developing an interest in landscape design. Ascending to the throne in 1694, Peter set Russia on a course of aggressive modernization (with the notable exception of political reform). He expanded the borders in campaigns against Sweden, invested heavily in industrial development, and built a sophisticated new capital city on the Baltic coast. Landscape architects from Western Europe were hired to design private gardens and parks for the nobility.

Island in the Swan Pool at Peter's Kadriog Palace, designed c. 1718.

Island in the Swan Pool at Peter's Kadriog Palace, designed c. 1718.

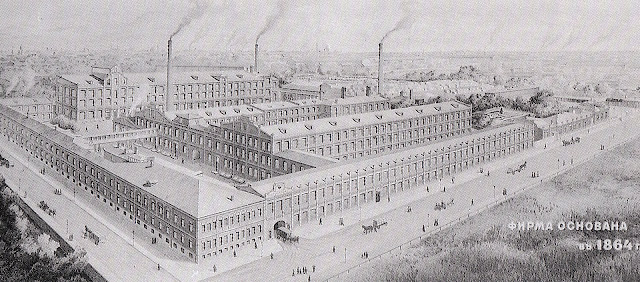

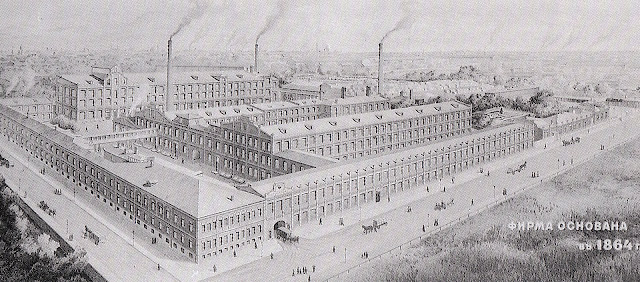

Factory in Moscow, 1864.

Factory in Moscow, 1864.

Moscow became an industrial center in the nineteenth century, and its population surged. The serfs were freed in 1861, but their treatment did not improve. There was a shortage of housing in the city, and health conditions declined severely. Early public parks were established, perhaps in an attempt to resolve the social and environmental problems that came with rapid urban industrialization.

Poster for the All-Russian League for the Campaign Against Tuberculosis, 1914.

Poster for the All-Russian League for the Campaign Against Tuberculosis, 1914.

The tsars were not equipped to manage modern development, and their limitations became increasingly clear during the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. Growing discontent set the stage for revolution. In my next post, I will focus on city planning ideas that emerged in the new socialist state.

Credits: Plan of Moscow c. 1600, plan of Apothecary's Garden, and photo of Swan Pool at Kadriog scanned from Russian Parks and Gardens, by Peter Hayden. Map of Moscow scanned from Muzhik and Muscovite, by Joseph Bradley. Illustration of carriage driver and tuberculosis poster scanned from Russian Graphic Design: 1880-1917, by Elena Chernevich. Photo of Moscow factory scanned from Mosca 1890-2000, by Alessandra Latour.

The second post in a series on public parks in Moscow, this is a brief visual exploration of urban development leading up to the October Revolution of 1917.

Map of Moscow, 1894.

Map of Moscow, 1894. Moscow's Kremlin was constructed in 1156 to protect the aristocracy, clergy, traders, and artisans living in its center at the time. The surrounding plains made the city highly vulnerable to attack, so expansion required protective embankments in the form of concentric rings. Moscow grew in stature as the great cities of Kievan Rus declined. Its grand princes (later known as tsars) led the resistance to Mongol rule, and the city was almost completely destroyed numerous times in the process. Russia managed to regain independence by the end of the fifteenth century.

Moscow proved very different from the relatively democratic cities of Kievan Rus. The grand princes ruled autocratically. In order to prevent other nobles from limiting their power, they gave land and laborers to a lower-order gentry in return for allegiance. Thus, serfdom was ingrained in Russia as it was falling out of practice in Western Europe. The landed gentry extracted income from their serfs and provided a military force for the tsars.

Illustration from an edition of Krylov's Fables, by Georgi Narbut.

Under this system, Ivan the Great and Ivan the Terrible strengthened the protective walls surrounding the Kremlin, Kitai Gorod (the market area east of the Kremlin), and Bely Gorod (White City, within the current Boulevard Ring); a new embankment was built around Zemlyanoy Gorod (Earthen City, within the current Garden Ring), and monasteries, estates, and artisan communities were established beyond the rings.

Plan of the seventeenth-century Apothecary's Garden at Izmailovo.

Plan of the seventeenth-century Apothecary's Garden at Izmailovo.Peter the Great spent much of his childhood at his father's Izmailovo estate on the outskirts of Moscow. He traveled throughout Europe, absorbing modern ideas and developing an interest in landscape design. Ascending to the throne in 1694, Peter set Russia on a course of aggressive modernization (with the notable exception of political reform). He expanded the borders in campaigns against Sweden, invested heavily in industrial development, and built a sophisticated new capital city on the Baltic coast. Landscape architects from Western Europe were hired to design private gardens and parks for the nobility.

Island in the Swan Pool at Peter's Kadriog Palace, designed c. 1718.

Island in the Swan Pool at Peter's Kadriog Palace, designed c. 1718. Factory in Moscow, 1864.

Factory in Moscow, 1864.Moscow became an industrial center in the nineteenth century, and its population surged. The serfs were freed in 1861, but their treatment did not improve. There was a shortage of housing in the city, and health conditions declined severely. Early public parks were established, perhaps in an attempt to resolve the social and environmental problems that came with rapid urban industrialization.

Poster for the All-Russian League for the Campaign Against Tuberculosis, 1914.

Poster for the All-Russian League for the Campaign Against Tuberculosis, 1914.The tsars were not equipped to manage modern development, and their limitations became increasingly clear during the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. Growing discontent set the stage for revolution. In my next post, I will focus on city planning ideas that emerged in the new socialist state.

Credits: Plan of Moscow c. 1600, plan of Apothecary's Garden, and photo of Swan Pool at Kadriog scanned from Russian Parks and Gardens, by Peter Hayden. Map of Moscow scanned from Muzhik and Muscovite, by Joseph Bradley. Illustration of carriage driver and tuberculosis poster scanned from Russian Graphic Design: 1880-1917, by Elena Chernevich. Photo of Moscow factory scanned from Mosca 1890-2000, by Alessandra Latour.